Biography

He was born on March 6th, 1926, in Suwałki, where he spent his childhood and early youth. During the war, his father, Jakub Wajda, a Polish Army officer was stationed in Radom. There, the teenage Andrzej Wajda took part in underground education and, for a short period of time, studied at a private painting school. At the same time, he worked as a warehouseman, porter, cooper, locksmith, and draftsman in a railway office.

After the war, he studied painting in Kraków (1946-50) and then directing at the newly formed Łódź Film School. He debuted in 1955 with the film A Generation which marked the beginning of his pursuit to realize one of his most important artistic and moral goals at the time – speaking on behalf of those who didn’t survive World War II. His following films Kanał and Ashes and Diamonds, made the 32-year-old filmmaker one of the most important European directors of his generation and launched the ‘Polish Film School’ (‘Polska Szkoła Filmowa’) movement, which explored Polish national martyrological tradition as well as romantic heroism.

During his over 60 years of multifaceted creative work, which included feature films, documentaries, TV movies, directing for the theatre, drawing, painting and screenwriting, the director made over 40 feature films. Many of them have become milestones in both Polish and international cinema. Appreciated by the global film community, he was nicknamed ‘the eulogist of difficult Polish history, which he was able to present as universal’; ‘the film poet of lost causes’; ‘the most important post-war Polish director’; ‘the chronicler of his country, a moral authority, a social critic with a camera’ as well as ‘one of world’s greatest filmmakers, who made the 20th century the great century of cinema’. Andrzej Wajda was considered a director who sought to intervene in Polish history with his films, turning ashes, bitterness and historical agony into works of art that shone like diamonds; and also, as an artist truly engaged in Polish freedom and democracy.

Film

After graduating from Łódź Film School Andrzej Wajda apprenticed with Aleksander Ford, working on his films Youth of Chopin and Five Boys from Barska Street.

He started his professional career in the times of socialist realism, yet he contrasted this style with piercing and morally complicated issues, which he raised in his first three films. They can be seen as a trilogy showing the drama of young people broken by the war and thrown into a new regime which faced them with unwanted challenges – sometimes even more difficult then fighting for their lives.

A Generation, Kanał and Ashes and Diamonds which describe the agony and divisions of Poland during and after the war brought him international recognition. Even in his early films the director came to be known as an observant author who captured the paradoxes and challenges of his time as well as an artist highly sensitive to form and symbolism, creating an original filmmaking style. Wajda repeatedly returned to the subject of war which shaped the fate of his generation, in films such as Lotna, Samson, Landscape After the Battle, The Crowned-Eagle Ring, Holy Week, Korczak and Katyń. The latter also marked his return to a personal trauma which he carried with him all his life: the director’s father Jakub was murdered in Katyń. With his desire to speak about the past, to keep its tragic memory alive and save those who gradually disappeared from oblivion, as well as with his imperative to do justice to the dead he spoke with one voice with Maria Janion, the author of To Europe: Yes, but Together with our Dead.

Book adaptations are a separate section in Andrzej Wajda’s filmography – visionary screen versions of Stefan Żeromski’s The Ashes, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz’s The Birchwood and The Maids of Wilko, The Promised Land based on the novel by Stanisław Reymont which was quickly globally recognized as a masterpiece, unforgettable adaptations of Fredro’s The Revenge and Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz, as well as Danton which was shot in France and Conrad’s The Shadow Line.

Throughout his entire career, working with the canon of classic literature, the director crafted a portrait of Poland in his compatriots’ collective identity and imagination. He painted its class divisions, symbols, and archetypes, and its ever-present past, filled with national demons. During times of intensified censorship, the texts chosen by Wajda allowed him to continue speaking about Poland in a piercing and critical way. Yet, each critique also served as an encouragement to step into the future, a future for which the Poles should take responsibility, breaking free from the national mold.

With his films, Andrzej Wajda always accompanied Poland’s recent history; moreover, they played an important and active role in the transformations of the 1970s and 1980s. Films such as Man of Marble, Man of Iron, and Wałęsa: Man of Hope, which were, as the director claimed, partly made “on the order of workers” who took part in the Solidarity movement, were called “Eastern Bloc’s Citizen Kane” by the Western press. These films depicted the workers’ unions as a movement of anti-state resistance and romantic patriotism. In Without Anesthesia—which was one of the flagship examples of the “cinema of moral anxiety” movement—Wajda focused on the organized mechanism of destroying extraordinary individuals by the state. This subject returned in the artist’s last film, Afterimage, which became the filmmaker’s testimony, filled with anxiety about Poland’s fate.

Yet another category in Wajda’s work is his personal, impressive films, composed of fragments of brilliantly observed reality, emotions experienced, and attempts to express the inexpressible. Wajda, who wove his language and cinematic sensitivity from memories of images he once saw, bits of light, subtle landscapes, overheard dialogues, and surprisingly apt metaphors, was unique in the way he spoke about passing (Sweet Rush) and the attempt to come to terms with both a sudden absence and a life that pours meaning into an empty, seemingly unfillable space (Everything for Sale). Films such as Innocent Sorcerers and Hunting Flies are also remembered as works that captured the spirit of a social revolution and the feverish pursuit of self.

Theatre

In the theatre Andrzej Wajda made himself known as a seasoned and attentive interpreter of Dostoyevsky, Wyspiański and Shakespeare, and his achievements on stage which consist of over 50 productions went down in history of Polish theatre.

He frequently worked in the theatre between making films, and his meetings with actors on stage often led to collaborations again on set—and vice versa. His first theatre production, in which he instinctively decided to use the talent of Zbigniew Cybulski, with whom he had worked on Ashes and Diamonds just before, was A Hatful of Rain at Teatr Wybrzeże in Gdańsk in 1959. This was followed by many more productions: Hamlet (four times), The Wedding, Demons, Danton, Nastasya Filippovna, Crime and Punishment, The Dybbuk, and Macbeth (twice). When he returned to the same texts, he did not repeat past adaptations but reread them on stage in a different way, depending on the people and circumstances, and looked at them from the perspective of the director’s and the audience’s present experiences. Wajda also worked abroad—in Stockholm, Weimar, Berlin, Tokyo, Moscow, Yale, and Budapest, among others. He considered Dostoyevsky his greatest teacher of both dramaturgy and human nature and said: “He was a visionary and the prophet of bad news. He knew how tendons stretch, he saw the dark side of our personalities, and unfortunately, he was often right in his criticism of the human being. Before Raskolnikov killed the old woman with an axe, he wrote a whole article to justify his crime. Many years later, when the world was immersed in blood, it turned out those crimes were also ideological: in Hitler’s Germany and the Soviet Union. Dostoyevsky predicted those murders as well—murders that found their justifications first, and then were committed.” Andrzej Wajda was most closely connected to theatres in Gdańsk, Warsaw, and Kraków, and for a period of time, he worked as the artistic director at Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw.

Civic activity

Andrzej Wajda was very much engaged in civic activity, not just making movies, but also initiating many important events, traditions and projects which transformed the Polish cultural landscape, and often went far beyond.

During the Polish People’s Republic, the secret police collected over a thousand pages of various documents (denouncing letters, transcripts from public and private meetings, reports, recommendations, etc.). Wajda was only deleted from it registers in July 1989, when he was formally a senator, elected in the first democratic elections since the war. The trilogy Man of Steel, Man of Iron and Man of Hope was a tribute to Solidarity and its leader Lech Wałęsa, as well as an attempt to explain its phenomenon and rationale to the world.

In 1987, after receiving the prestigious Kyoto Prize, known as the ‘Japanese Nobel Prize,’ Andrzej Wajda, who was known for his affinity for Japanese art, founded The Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Kraków. The museum hosts the collection of Japanese art assembled by Feliks ‘Manggha’ Jasieński—a traveler and collector who donated his possessions to Kraków in 1920. Wajda fell in love with the collection when he was a young student at the Fine Arts Academy in Kraków. It was the first post-war Polish museum that was privately financed in full and is now the largest treasury of Japanese culture in Central Europe. There are over 10,000 works of art and craftsmanship on display.

Andrzej Wajda was also the originator and initiator of pavilions dedicated to Stanisław Wyspiański and Józef Czapski, where – with the help of Krystyna Zachwatowicz-Wajda and the National Museum in Kraków which acted as a curator – works and objects connected to the life, works and memory of these distinguished artists were collected.

He was also the initiator of many cultural projects like the Contemporary Art Centre Elektrownia in Radom, which he supported together with his wife, donating many precious works of art from their own collection. He also organized many exhibitions and initiatives abroad, aiming to promote Polish artists and their achievements. Wajda dedicated his time to helping communities he felt ideologically bound to, even when he held various responsible and prestigious positions. As the chair of the Polish Filmmakers’ Association, he negotiated new rules for how the cinema industry was to function in Poland—particularly regarding the independence of movie production and the reduction of censorship. He took part in preparing Lech Wałęsa for his debates with opponents, and during the campaign leading up to the first democratic elections in 1989, he supported opposition leaders both in terms of content and image. He was also elected senator in those elections. Additionally, Wajda was active in the fight for free media—at his house in the Warsaw district of Żoliborz, the contract was signed that led to the creation of the Agora company, publisher of Gazeta Wyborcza, the first independent daily newspaper in Poland after 1989. Wajda was one of three signatories of the deal.

Pedagogical activity

Pedagogical activity was also an important area of Andrzej Wajda’s work.

In the 1960s, he lectured at the Directing Department at the Łódź Film School. He was the initiator of the production studio Zespół Filmowy X and its artistic director. In 2002, he founded the Andrzej Wajda Master School of Film Directing, which continues to operate successfully to this day (now known as the Wajda School) and has educated many filmmakers who became important figures in Polish documentary and fiction cinema. The Wajda School has produced hundreds of student films, many of which have been screened at major film festivals. Thanks to its open, interdisciplinary, and collective formula—drawn from the earlier Zespoły Filmowe—the school allows candidates with interesting achievements, not necessarily in film, to carry out projects under the supervision of experienced and widely respected teachers, who are also active filmmakers. In his last will, Andrzej Wajda wished for the royalties from his films to be allocated for scholarships for talented youth.

Awards

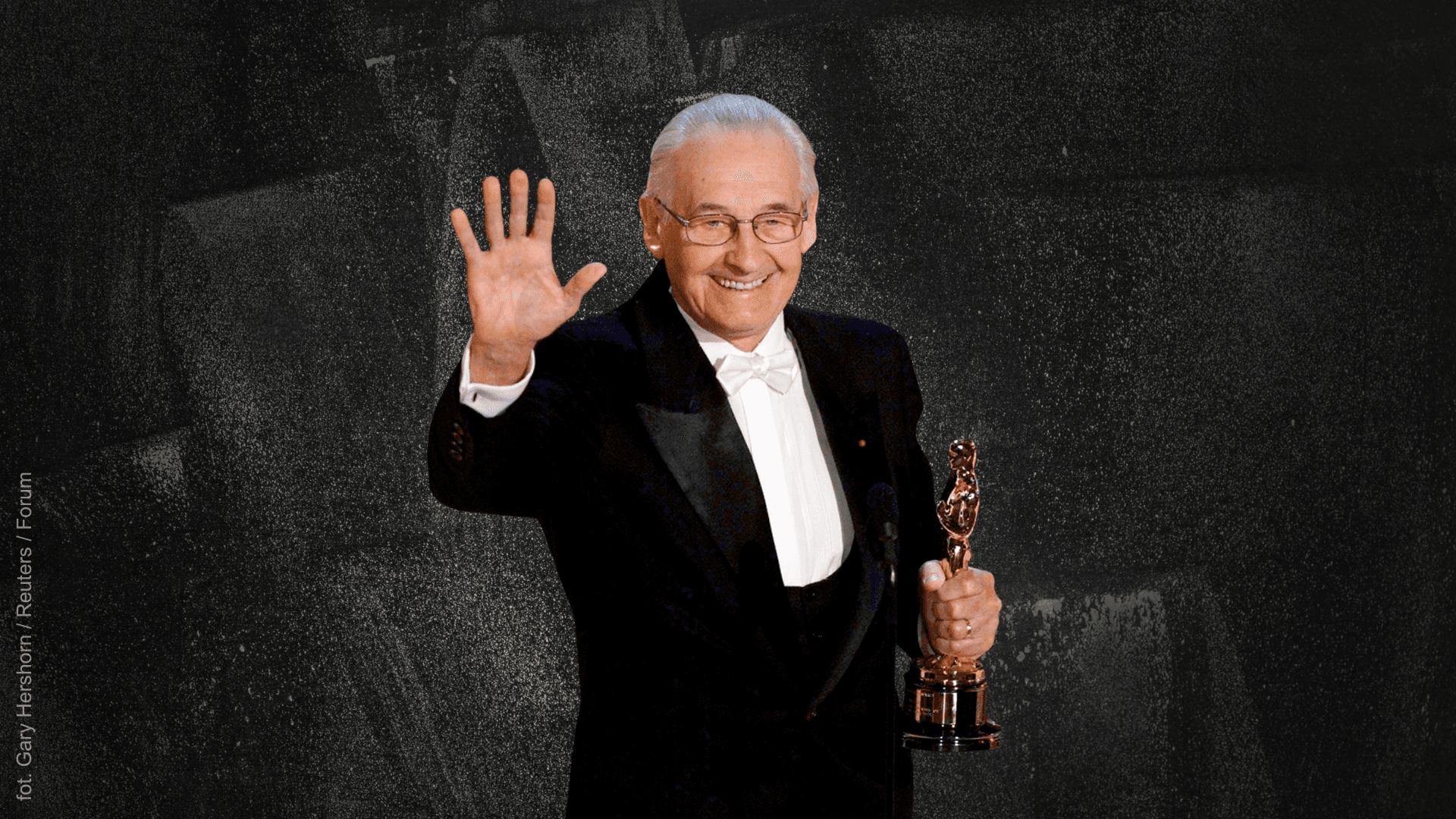

Andrzej Wajda is the recipient of many Polish and international awards, distinctions, decorations, and honours for both his artistic and social work.

His most important prizes stem from his participation in prestigious festivals and include, among others: the Palme d’Or and Special Jury Prize at Cannes, FIPRESCI awards, Golden Lions in Gdańsk, four Oscar nominations and the Academy Honorary Award, César, European Film Award Felix, Golden Lion at the Venice IFF, Platinum Lions at the Gdynia Film Festival, Golden Bear at the Berlin IFF, lifetime achievement awards at the Sevilla and Plus Camerimage film festivals, the Polish Filmmakers’ Association Award, and the Golden Duck.

The highest state awards he received include, among others: the Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta, the Japanese Order of the Rising Sun, the Bulgarian Cyril and Methodius Order, the Komturkreuz of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Commander of the Legion of Honour, and Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in France, the Commander’s Cross with Star of the Hungarian Order of Merit, the Ukrainian Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, the Golden Medal Gloria Artis, the Order of the White Eagle, the Kyoto Prize awarded by the Japanese Inamori Foundation for his work in the development of science, technology, and human thought, and the Great Prize of the Culture Foundation. The director was also awarded honorary doctorates from many institutions, including the Fine Arts Academy in Warsaw, American University in Washington, the Polish National Film, Television, and Theatre School in Łódź, Jagiellonian University, the Film Academy in Moscow, Belarusian Fine Arts Academy, and Pedagogical University of Kraków. He was also an honorary member of the French Academy of Fine Arts.