Filmography

Andrzej Wajda was a highly prolific artist, interested in more than just cinema. However, it is through this medium that he became a distinguished personality among Polish artists.

He made nearly 60 films: features, documentaries, anthology films, and numerous television plays. In the introduction to the book that accompanied an edition of his collected works—a gift to the master on his 90th birthday—Andrzej Wajda wrote:

‘My films were made over several decades, in different eras of cinema. I tried not only to participate in the political events of our country, but also to take part in the evolution of European cinema. Thanks to Cybulski, in Ashes and Diamonds, I embraced new American methods of acting. I wasn’t alone, and Polish films made their mark on the world, moving foreign audiences despite the language barrier and our difficult past. (…) I would like to express my gratitude to those who fought for the conditions that allowed our films to thrive. Right after the war, our film industry gradually became part of the struggle for political and artistic freedom. It was consistent in expanding this freedom—from Aleksander Ford and Wanda Jakubowska, through Jerzy Kawalerowicz and Jerzy Bossak, to the fight for cinema’s survival during martial law in the 1980s. I am fortunate to have been part of this process—with my films and the artistic authority of a director.’

In the notes below, which provide a summary of Wajda’s films and their reception, the fight for artistic freedom emerges as a central theme. We hope that by reading them, those who are only just beginning to discover our patron’s work will gain a better understanding of his passion for expressing both the European psyche and our own Polish identity—complicated, marked by many shocks and paradoxes.

‘The generation described by Czeszko in his novel was not mine. And yet, I associated the title of the film with the first generation of Polish filmmakers who graduated from the Łódź Film School. We were all debutants on this film,’ said Andrzej Wajda about his first feature, based on Bohdan Czeszko’s novel. The film, made in 1954, gained praise and is considered one of the first examples of the Polish Film School.

In many contemporary critical reflections, the film is criticized for being based on social realist literature. Initially, the novel, which was awarded the National Prize, was to be adapted by the ‘grey eminence’ of the Polish film industry, Aleksander Ford. In the end, he entrusted the project to his former student Wajda. There are speculations that the reason was the mediocre grade the text received from the verification commission. Nonetheless, it was a great honor for the young director, and it allowed him to assemble a remarkable crew, mostly made up of debutants. Together, they transformed a ‘program’ book into a film that surpasses the original in artistic, narrative, and psychological depth.

What’s more, the recent war experiences of the crew and the location in Warsaw—still rising from the ruins—added an authenticity that foreign critics compared to newsreels. Even though it’s easy to detect propaganda content and tone in A Generation, when compared to other first-time features of the time, it becomes evident that this story about left-wing youth engaged in conspiratorial fights with the occupier, searching for their own way in a time when people believed they could shape the future ‘here and now,’ cannot be called a socialist film.

A great asset of the film was the introduction of many young actors who would soon become the leading figures in Polish theater and cinema. The acting styles of Tadeusz Łomnicki, Tadeusz Janczar, Zbigniew Cybulski, and Roman Polański—who, despite his directing career, continued acting throughout his life—were something new, completely different from the pre-war method. They made the protagonists feel moving and real. These were the same boys the audience could encounter at work, on the street, or in a yard, speaking in a familiar, sometimes clumsy, informal slang, devoid of the unnatural mannerisms typical of actors. The problems they spoke about were the worries and dilemmas shared by all Poles.

‘In A Generation, we showed the workshops I worked in during the occupation, tenements, and poor suburban streets where I lived during the war. It was important for me to place a heavy burden on my protagonists’ shoulders—these boys from the suburbs and their parents, workers from the Wola and Koło districts. The occupation was a failure for our nation, but their lives were never carefree or beautiful. That’s why our boys are normal—not cut out to be heroes,’ Andrzej Wajda recalled.

Other filmmakers who later became great personalities of Polish cinema also contributed to making A Generation. Kazimierz Kutz, who later became a eulogist of his native region of Silesia and a respected theatre and film director in his own right, worked as assistant director, while cinematographer Jerzy Lipman later worked with Andrzej Munk, Aleksander Ford, Jerzy Hoffman and Roman Polański. He was very much inspired by the the philosophy of neorealism: with Wajda they created a scenery of roaring workshops, cheap bars and dirty streets shot in an expressive way.

A Generation came to be the first part of Wajda’s trilogy about the dramatic experience of war; it was also a testament to the director’s fondness for distinct characters troubled by doubt and tragic choices, living an initiation that gave them a bitter awareness of the fact that clear victory, reason, or truth do not exist.

‘In this canal my teenage illusions died’ – said Jerzy Stefan Stawiński, alias Łącki, a soldier in the Warsaw Uprising, lieutenant of the Polish Army. On September 26, 1944, as the leader of the signal company of the ‘Baszta’ regiment, he led seventy people into a canal with the hatch on 6 Szustra Street in the Mokotów district. The next day six survivors exited the canal on the crossroads between Aleje Ujazdowskie and Wilcza street…

Writing the story of the soldiers’ ordeal, coincided in time with historical events that allowed for its publication and helped pave its way on to the screen. In 1956 during the XX Congress of the CPSU in Moscow, Nikita Khrushchev disclosed some of Stalin’s crimes, while Bolesław Bierut had died a few months before. Stawiński published the short story describing the insurgents’ tragedy in March 1956 in Twórczość monthly. A month later, under the amnesty, numerous former Polish Army soldiers were released, and a large part of society demanded their vindication and recognition of their merit and bravery in the unequal fight with the occupant. It was also important for the families of the victims and the survivors to see the lives of their loved ones as an element of the story of this traumatic time, even if it were to be just the story of their martyrdom, and not their moral victory. For political reasons Aleksander Ford opposed the idea of adapting Stawiński’s text for the screen, yet Konwicki, Toeplitz and other young intellectuals backed it.

At first Andrzej Munk prepared for making the film, yet after he went in the sewers, he decided what was supposed to be the essence of the film, is actually impossible to express: ‘What’s the most important thing about the canal? The darkness, of course. If we go down there with the lights, it is not going to be dark anymore. (…) The other thing is the awful smell. How do we show it in a film?’ – he asked Janusz Morgenstern, whom he asked to assist him. Finally, he withdrew from the film.

Andrzej Wajda recalled: ‘Tadeusz Konwicki was the godfather of my first and most important success, which was Kanał. He gave me Stawiński’s short story and as the literary director of the Kadr film studio he did everything in his power to make this film possible. He also lobbied for the screenplay when working in the committee that evaluated films and screenplays (…) From the first time I read the short story, I knew I would be making a film that was important to me. I just wasn’t sure if I would be able to present an image that would be potent and convincing enough. It’s hard to imagine what Kanał’s fate would be, if not for the surprising decision made by the cinematography chair Leonard Borkowicz, to show the film at the Cannes film festival. It was even more surprising due to the fact he was the one who had the most reservations and was very skeptical about making the film at first’.

At the Cannes Film Festival, many American writers and producers asked Jerzy Stefan Stawiński how he came up with such a brilliant dramaturgical idea to bring his protagonists into the sewers. The Silver Palm award the film received (shared ex-aequo with Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal) brought him international recognition, while for Polish moviegoers – some of whom, just over a decade earlier, had taken part in the Warsaw Uprising and lost loved ones – Kanał was the first film to honor the truth and memory of the defeated heroes.

The film was shot in a sewer constructed in a studio on Łąkowa Street in Łódź. In the group scenes set in Warsaw, soldiers from the Kościuszko Infantry Division appeared. The tanks the army rented for the crew were used to portray the Wehrmacht’s munitions – their shots even broke the windows of buildings surrounding the set. Kazimierz Kutz, who worked as Wajda’s assistant, recalled: ‘Nobody protested, since people knew we were making a film about the uprising. All the glaziers from Warsaw came to the rescue.’ Kutz also recalled Wajda’s hesitation, knowing how important the subject matter was. Wajda spoke about the making of the film: ‘We knew we were the voice of the dead; we knew our duty was to give testimony to these awful years, the terrible destruction, the awful fate of the Poles – the best of us. We wanted to make films that would help change our country. It was the strength of Polish films, as well as the incredible social energy of the moving image, that spoke to the world about us and the tragic experiences of people living in a certain Eastern European country behind the Iron Curtain.’

Expectations for the film among various audience groups were so different that it was impossible to satisfy everyone. Some people found it too symbolic, while others thought it was too real and didn’t convey every meaning. Some criticized the psychology of the characters. Yet, there were also positive reviews. Stanisław Grzelecki wrote in Życie Warszawy after the premiere: ‘There are two ways of looking at Kanał: either as an artistic report from an event or as an attempt to generalize people’s tragedy. In both cases, a part of the audience will not be able to free itself from the burden of personal memories. I am one of them. I walked the same underground path from Mokotów to Śródmieście as Jerzy Stawiński, and just as he did, I spent seventeen hours in the sewers. I saw and experienced enough to say that Wajda’s film tells the truth. The general tone and atmosphere are realistic, as are individual episodes. I could give examples from real people’s lives – just as many who shared the same path – which would confirm almost every minute of this part of the film… The tragic fate of those who believed in the righteousness of the fight is movingly reflected in Wajda’s film. The drama becomes an even more suggestive metaphor, since its protagonists were for years pushed into darkness, into silence, into a mire of unjust accusations and defamation.’

The film’s international success, which began with the prize at Cannes, gradually changed the Polish audience’s opinion about it. In the first year of screening, 4.2 million people went to see it, and Kanał remains one of the most recognized Polish films in the world to this day.

The true dimension of Ashes and Diamonds is eschatological because the film’s true passion is not that of a meticulous historian, but of a moralizer who speaks about the most essential things: life and death, beauty, love, and the nightmare of taking someone’s life. Even if Wajda’s intentions were different, his talent controlled them, and critics should always remain faithful to the talent. There is a scene in Ashes and Diamonds where two people—the victim and the murderer—walk toward each other and fall into each other’s arms, as if seeking salvation from something else, from destiny. This is the true summary of the film—a summary that evokes not Wyspiański or Styka, but Aeschylus and Shakespeare,’ wrote Stanisław Grochowiak in Ekran magazine after the premiere. His words seem to explain the phenomenon of Wajda’s film, which many consider his greatest accomplishment, shot when he was only just beginning his career, at the age of 32.

Ashes and Diamonds, Jerzy Andrzejewski’s novel, published three years after the war, was a set book in Polish schools during the communist era, supported by the government. Prominent figures such as Erwin Axer and Antoni Bohdziewicz had considered adapting it for the screen. Andrzej Wajda first heard about the novel from Tadeusz Janczar and Janusz Morgenstern. In November 1957, the director and the novelist met and began working on the script, modifying the literary work to preserve the unity of time. A few months later, the screenplay was accepted for production. Initially, Wajda wanted to cast Tadeusz Janczar, with whom he had already worked on A Generation and Kanał, but Janusz Morgenstern suggested Zbigniew Cybulski for the role of Maciek Chełmicki. This choice turned Cybulski into an icon of the new generation and became one of the pillars of the film’s success. Cybulski brought with him an intuitive style of acting based on improvisation. Thanks to his decision to wear his own clothes—which didn’t fit the intended costume design, as they were ten years more modern than what people wore immediately after the war—and his refusal to take off his dark glasses, which he felt comfortable in, the role of Maciek Chełmicki has remained timeless. At the time, it was one of the first examples of a truly modern acting style, to the point where Cybulski became so closely associated with this role that he struggled to break out of his rebellious persona until he matured as an actor.

After three months of shooting and post-production, the film received permission for distribution, thanks to the mediation of Andrzejewski himself. However, decision-makers found it difficult to accept Chełmicki as the film’s main protagonist. Wajda’s former mentor, Aleksander Ford, also lobbied for a ban on distribution. The party also blocked the film’s participation in festivals. Yet despite all that, it was enthusiastically received by critics, both in Poland and abroad. According to many, it became the most famous Polish film in the world and the flagship work of the Polish Film School—a group of filmmakers influenced by romanticism and symbolism, focused on the wartime experiences of the young generation of Poles. In the year of its premiere, over 1.5 million people saw the movie in Poland.

Ashes and Diamonds had a profound influence on the history of Polish cinema, sparking controversy among other directors from the Polish Film School. In 1960, Kazimierz Kutz directed the ‘antithesis’ of Wajda’s film, Nikt nie woła (Nobody’s Calling), where the protagonist, also an underground Polish Army soldier, decides not to execute the order but instead to start a new life. In his great work How to Be Loved, Wojciech Jerzy Has made a pastiche of the legendary ‘lamp scene.’ After the war, the main protagonist enters a bar, where the song Czerwone maki na Monte Cassino plays, but it is sung by an elderly woman who looks like a cocotte, while Cybulski’s character is a drunk who recalls his invented heroic deeds.

Many years later, Andrzej Wajda described the tragic paradox that led him to adapt Jerzy Andrzejewski’s novel in his own way, according to his own conscience and motivations: ‘The fate of the boys from Kanał, Tadeusz from Landscape After the Battle, Marcin from The Crowned-Eagle Ring, and Maciek Chełmicki from Ashes and Diamonds could easily have been mine. I just had more luck. It was by chance that I avoided their situation, and so I felt it was my duty to tell their stories to the best of my abilities. The never-ending discussion about what Ashes and Diamonds is as a novel and what it is as a film adaptation doesn’t clearly point to an important motive. In the novel, Jerzy Andrzejewski aimed for a national consensus; he tried to convince his readers that even though Poland was politically divided, and the division ran deep, one had to seek agreement. This aim is clearly seen in the last scene of the novel, where Maciek Chełmicki falls, and the soldiers come to him and ask: ‘Boy, why did you run?’ For Andrzejewski, this was a real question: ‘Why did you run?’ If you hadn’t run, you might have had a chance to live. When we shot the film in 1957, we already knew what it meant. Both Zbyszek Cybulski and I knew well why Maciek escapes—we understood that he had to escape. We realized that nobody really wanted a consensus, and that it was impossible to reconcile.’

Lotna premiered in September 1959. Despite the title, it is not a film about a very special horse, but the third film—after Stanisław Różewicz’s Wolne Miasto (Free City) and Leonard Buczkowski’s Orzeł (Eagle)—to tell the story of the September 1939 tragedy, which was not discussed in film for over a decade after the war. Yet, in contrast to both previous films—especially Różewicz’s feature, which was almost a paradocument—Wajda’s movie refers to a legend, a myth, and a stereotype. After A Generation, Kanał, and Ashes and Diamonds, it was his fourth feature. ‘I needed a film about the cavalry to end the subject of war,’ the director recalled many years later. In a sense, the cavalry was the essence, the substance, and the pride of the Polish army during the time of the Second Polish Republic. It’s hardly surprising that Wajda said his aim was to make a ‘sad, almost watercolor film about uhlans in Kutno. About a beautiful, pointless tradition,’ wrote historian Jerzy Eisler about Lotna.

The film, an adaptation of Wojciech Żukrowski’s novella, is actually a story about the ethos, symbolism, and values of a world passing into oblivion. The author himself appears in the film as a soldier resting in a stable. Lotna was shot on ORWO color film, but due to shortages, the final sequence was shot in black and white. After the film’s premiere, a discussion arose about the vision and judgment of September’s failure, which divided Polish society. However, the director’s aim was not to document the subsequent stages of this failure but to create a symbolic impression, set in September, that showed something completely different: a portrait of a hermetic world standing against time, immersed in the pre-war romantic myth symbolized by the horse in the film’s title and the Polish cavalry.

The director recalled the film’s premiere: ‘Early in the morning, after the film hit the screens, I was full of trepidation when I sat on a bench in Ogród Saski with journals on my lap. All the reviews were crushing. Surprised by this turn of events, I thought: Lotna failed, and I didn’t need the press to tell me about it. I struggled with the script, with the cast, and the production for months, and was completely aware of that. And yet… it is my film, and no one else could have directed it. So maybe my flaws are more original than my assets. Or at least they are mine, and I should defend them even from myself.’

The film was accused of being ‘all poetic form and no substance,’ of forging historical truth, and of making the audience indifferent by not focusing on the protagonists—although many critics appreciated the director’s struggle with the artistic matter. In foreign reviews, there was praise for the work’s baroque style, its artistic mastery (Lotna was compared to von Sternberg’s The Scarlet Empress, Welles’s The Process, and Fellini’s 8½), and the director’s invention. Various paintings were noted as inspirations, as well as their masterful use in the film—a technique that would become a signature element of Wajda’s directing style. Zygmunt Kałużyński wrote that Lotna is a cross between surrealism and Polish Uhlan tradition, as well as ‘all the props of our 19th-century battle painting.’ However, surrealism was viewed with suspicion in socially realist Poland as a trend that distorts and profanes reality. The analogy with how Wajda treated the historical truth about September 1939 was more than obvious.

‘With Lotna, Wajda flew high as an artist, but he didn’t cope with himself as a director,’ Dariusz Chyb wrote in an essay about artistic inspiration in Wajda’s films. ‘His fourth film is a failed masterpiece; crippled, unfinished, like many works in the history of art. It’s like a genial sketch for a painting that never came to be. But there is something very charming about what’s sketchy—just as in all the unfinished romantic poems.’

Innocent Sorcerers is now seen as one of the most politically neutral films I have ever made. Yet, that wasn’t the case in the times of Gomułka. This innocent theme of a young doctor who likes elastic socks and good cigarettes, owns a tape recorder, and records his conversations with girls, who’s only passionate about playing the drums in Krzysztof Komeda’s jazz band—it was more controversial for the ideologists than the Polish Army and the Warsaw Uprising,’ said Andrzej Wajda about his fifth feature, shot in 1960, co-written with Jerzy Andrzejewski and Jerzy Skolimowski.

That’s what Janusz Wilhelmi—politician and Wajda’s fiercest critic—wrote about Innocent Sorcerers in Trybuna Ludu: ‘For most of the audience, especially the young ones, the social critique will be almost invisible. But the free lifestyle, which is presented so alluringly, will be much more seductive. And this can be seen as socially harmful.’

The aim of one of the film’s screenwriters, Jerzy Andrzejewski, was apparently to capture a new way of being and the new phenomenon of ‘social egoism’ among young people, which consisted in hiding their feelings, nihilism, and a cynical, anti-metaphysical view of reality. The title was borrowed from Mickiewicz’s Dziady, Part I:

‘Such seclusion’s been sought out by the fervent sage

Intent on finding wealth, medicinal balm,

Or poison… We, young innocent sorcerers – let us test the scope.’

It may come as a paradox that some advocates of the film, who appreciated Wajda’s versatility when it came to style and subjects, believed the film to be an accusation of the protagonists’ behavior. Critic Stefan Morawski wrote in a review published in Ekran magazine: ‘The film is socially useful. And I believe—although the intentions of its creators might have been objective—it is an accusation. The accusation has been weakened by the unnecessary ending (Pelagia’s return), yet the moral bankruptcy of the way of life we see is evident enough. The film is alarming, since Bazyli and his peers scare us with their emptiness and passivity. It’s alarming, if not for the young themselves (who are not innocent sorcerers at all), then at least for the adults.’

International reviews were favorable—the film was associated with the style of the European New Wave, and critics noted how it distanced itself from the wartime experience, focusing instead on the love life of the young generation and their values. Yet the film received much criticism in Poland: Polish Catholic Church deemed it completely unfit for young audiences due to its helplessness in the face of the problems it presented and its lack of educational advice. This opinion was included in a letter Wajda received in early 1960 from the Department of Pastoral Assistance of the Archdiocese of Warsaw. The film was also attacked by the Polish Communist Party, which deemed it to be promoting a way of life devoid of any healthy ambitions and goals.

Innocent Sorcerers is one of Wajda’s most surprising films, not easily associated with his usual style or the subjects he typically explores. This intimate story, faithful to the classical unities of time, place, and action, its formally minimalistic style reminiscent of cinéma vérité, contemporary themes, modern music by Krzysztof Komeda, and Tadeusz Łomnicki’s acting style, make it a film that achieved cult status in certain circles. The director thought the story might have been even more modern if he had cast one of the writers, Jerzy Skolimowski, in the leading role, and his wife, Elżbieta Czyżewska, as Pelagia—they were one of the ‘power couples’ of Polish cinema in the 1960s. Yet, the audience and some modern critics believe the film captured a sense of being stuck in ‘little stability’—a lack of perspectives, goals, and ideas—that resonated with the young generation. Paradoxically, the more time has passed, the more praise the film has received: today, its title serves as the name of festivals, music clubs, and restaurants. It remains a constant reference point in Polish popular culture, and 60 years after its premiere, it continues to find new audiences. Abroad, its fame doesn’t fade either: Martin Scorsese, a great admirer of Wajda’s talent, considers Innocent Sorcerers to be one of Poland’s greatest masterpieces. In 2014, he included the film in his review shown in the USA and Canada, entitled Martin Scorsese Presents: Masterpieces of Polish Cinema.

The novel Samson was written soon after World War II as part of the Między wojnami (Between the Wars) tetralogy, which also included Antygona, Troja. Miasto otwarte, and Człowiek nie umiera. Kazimierz Brandys strongly identified with the protagonist of Samson, even giving him his own date of birth. When the rules of social realism for artists were loosened in 1956, he went on to write a film adaptation of his novel, which received positive reviews from cinematography authorities. The screenplay was written independently, without consulting Wajda, yet the director of Ashes and Diamonds quickly contacted the writer and told him he wanted to adapt his work for the screen. Brandys envisioned a fully realistic movie; Wajda, in contrast, chose to approach Samson with a monumental picture in mind.

‘When I was reading Kazimierz Brandys’s novel for the first time, I had hopes for a contemporary biblical parable. But the novel demanded simplicity and modesty from the director, and most importantly—attention to detail. From the first day of shooting to the last day of editing, I was torn between these two extremes. After making Ashes and Diamonds, both Jerzy Wójcik (the cinematographer) and I knew the power of cinematic abbreviation and the use of symbols on screen. We wanted to pursue this path, yet the novel resisted our ideas and defended itself as much as it could,’ said Andrzej Wajda years later about his approach to adapting the work of the author of How to Be Loved and Mother of the Kings.

Wajda searched for a young, Semitic-looking actor for the lead role at film schools and universities, but he didn’t find anyone he wanted to work with. Many years later, he pointed out that the Holocaust in Poland was such a total force that it caused a certain type of beauty to vanish. ‘It’s proof that it was the destruction of a whole nation,’ Wajda said. ‘I just couldn’t find anyone who looked right among students at the time, so I decided to cast a French actor who was the opposite of Samson.’ The role was played by Serge Merlin, and the supporting cast included Roman Polański, Zdzisław Maklakiewicz, Edmund Fetting, and Bogumił Antczak.

The tragedy of a young fugitive from the ghetto, struggling with fear and a sense of alienation against the backdrop of occupied Warsaw, who decides to end his life in a suicidal gesture that also kills the occupiers, was filmed by Wajda with visual finesse and mastery, which led to a nomination for the main prize at the Venice Film Festival. However, the way he told the story was brutally criticized. ‘In Wajda’s world, everything is upside-down, like the Christ from Ashes and Diamonds. Everything is just decoration. Wajda is only interested in photogenic faces, objects, stories, and problems. He always wants to make his own deal: to show everyone how talented he is. Yes, he is. But he lacks taste and thought. If he’s really a master of a school, this school should burn, because it teaches coquetry, narcissism, irresponsibility,’ wrote Andrzej Kijowski in Przegląd Kulturalny.

Years later, Wajda himself decided not to include Samson in an anniversary edition of his works. After the film’s premiere, Konrad Eberhardt wrote in Film magazine about the reception and contrasting opinions of the movie, trying to separate its artistic meaning from the psychological and historical layers: ‘People didn’t really strain their brains when criticizing Samson. The same objections were mentioned in most reviews: that the film is false in showing this or that, that the protagonist is not representative enough, and that the film does not carry its burden well enough, that the subject of the ghetto is still waiting, and so on. Nobody really tried to interpret this new proposal from Wajda—so different from what he’s done before—on an artistic level (and not a journalistic one), thinking about the artist’s goals and his values.’

Perhaps because of this confusion and dissonance between different interpretative layers, as well as a sense that it didn’t resonate with the audience as strongly as Wajda’s previous works about the tragedy of war, Samson is now one of the least-known films by Andrzej Wajda.

‘When working on Siberian Lady Macbeth, I lacked a distinctive idea and a cinematic grasp. I realized I needed a dramatic move that would present the story of the unfaithful killer in retrospect, making the procession of convicts to Siberia the central plot. The life of the laborers, their unusual customs, and surprising scenes from literature – such as the bell that was convicted and sent to Siberia for not playing the right sound – would make for great material. I also considered incorporating the topic of Poles exiled to Siberia, as well as protagonists and situations from Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead. There was so much to show on screen!’ – Andrzej Wajda recalled his idea for the film, which was an adaptation of Nikolai Leskov’s short story published in 1864.

Great Shakespearean dramas, as well as Dostoevsky’s novels, posed a challenge for Wajda, who returned to them many times throughout his career. This was the case with Hamlet, which he worked on four times, as well as with Dostoevsky’s novels, which captivated him with the extreme experiences of their protagonists, their insightful and moving depiction of the anatomy of evil, and their portrayal of systems and ideologies that sanction it. He was also drawn to the protagonists’ journey toward self-awareness, a path filled with suffering and struggle. Shakespeare was another of his fascinations, guiding his readers through the deepest and darkest recesses of human nature.

Wajda successfully staged Macbeth twice in the theater (in 1969, with Magda Zawadzka and Tadeusz Łomnicki, and in 2004, with Iwona Bielska and Krzysztof Globisz). However, it was in Siberian Lady Macbeth that he first touched upon the subject on film, setting the story in 19th-century Russia.

Shot in 1962, Siberian Lady Macbeth was one of the few films Wajda directed abroad. Made in collaboration with a Yugoslavian crew and cast, Wajda hoped that working in a foreign country would inspire new artistic possibilities. Yet, as he recalled many years later, his hard work resulted in ‘beautiful cinematography by Aca Sekulović, Syergiej portrayed with heart and talent by Ljuba Tadić, and set design.’ Nevertheless, the film made the director realize how difficult it was for him to find his place in a foreign country. The creative freedom he felt abroad did not make him feel as comfortable on set as he did in his homeland.

The film was well-received internationally, though the director himself was not satisfied. A review published in Sight and Sound praised the change in cinematic style – moving from a baroque form to a simpler, more modest way of telling the story of a woman who killed for love. Critics also lauded how the film captured the spirit of the time and place, as well as the timeless atmosphere that accompanies every universal tragedy. Variety complemented the Slavic character of the film, reinforced by sophisticated imagery, precision in working with actors, and the use of excerpts from Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera, based on the same literary material.

Cinematographer Aleksander Sekulović, whom Wajda praised, and lead actress Olivera Marković were awarded at the Yugoslavian Film Festival in 1962. It seems that international cinephiles revisit this film – which the Americans called ‘a Russian-Shakespearean noir’ – more often than Polish fans of Andrzej Wajda’s talent.

‘Beginner Parisian producer Pierre Roustang, after a film with Basia Kwiatkowska (then Lass), decided to produce a series of moving images about ‘love in different countries.’ It was meant to be a portrait of contemporary youth. France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Poland participated in the project,’ Andrzej Wajda recalled about the anthology project L’amour à vingt ans. François Truffaut (who had the task of inviting other directors), Renzo Rossellini, Marcel Ophuls, and Shintaro Ishihara also contributed to the project. Jerzy Stefan Stawiński wrote the Polish episode, while the leading roles were played by Barbara Kwiatkowska-Lass, Władysław Kowalski, and Zbigniew Cybulski. The score was composed by Jerzy Matuszkiewicz, Andrzej Żuławski served as the second director, and Jerzy Lipman was responsible for the cinematography.

Wajda came up with the idea for the script after hearing about an event in passing: ‘By chance, I heard about an incident reported in a local paper in Wrocław. At the zoo, an anonymous man rescued a child who had fallen into the cage where polar bears lived. The child was fine, and the rescuer disappeared into the crowd that gathered after the accident. That’s all I knew. To my mind, this protagonist had to be Cybulski. He had changed since Ashes and Diamonds – he had put on weight and lost his boyish figure, but he was supposed to play himself, only later: someone who survived the war and is now forgotten and alone. After a lost war, as I had shown in Lotna and Kanał, the subject of a lost life came to mind.’

Only four years had passed since Ashes and Diamonds, yet the actor, who was 35 at the time, convincingly portrayed a man permanently scarred by the war, clearly different from his younger peers. Cybulski would go on to play other great roles, but this was the last time he worked with Wajda on set, a collaboration the director would deeply regret after Cybulski’s death.

Through the combined artistic forces of five directors, a diverse film was born, offering a sketch of a generation entering adulthood, becoming cynical and resigned while gaining life experience. Even though Wajda’s episode was short, it was highly praised as a standout piece, masterfully using mental shortcuts, symbolism, and sharp vision. The French review Positif wrote: ‘In what could have been yet another cliché about the timeless generational conflict, or worse, a malicious pamphlet against the egoism of youth, Wajda was able to achieve a brilliant balance. Instead of glorifying the heroism of the former soldier confronted with contemporary shallowness or condemning the young into the fatality of the times, he was courageous enough to confront them: the braveness and complacency of a man who’s been written off, with the instinctive cruelty of the young, and with the awkward, sincere sensitivity of the girl. Mastery after babble, sharpness after vague obsessions – it’s one proof against four, but enough for a hundred, of the pretentious void of our nouvelle vague.’

For Wajda, the film became a valuable lesson about the passage of time. He understood that his sympathy and identity lay with Cybulski’s character, the man whom he described as ‘a mediocre man who doesn’t expect much from life,’ and, most importantly, someone for whom the war was a formative experience. He noted: ‘That’s when a new generation grew up, one that didn’t remember the war. … With these young people around us, a new element of play entered our lives. And so, fun became the subject of the movie as well. We had to keep cruel visions of executions – as seen in Andrzej Wróblewski’s paintings – and wartime fears for ourselves, leaving the joy to the young. … Our combatant past didn’t interest anyone anymore. What was even worse, new filmmakers entered the stage, and I was surprised to learn that I was no longer the youngest director in Poland.’

‘The first feeling I got was fear at the thought that I am part of the same nation whose deeds I see on screen. Would anyone else have such cruel courage to show his nation this way? I don’t know anyone in the whole world capable of such an awful exhibition, of such a presentation: look at us, how cruel we are, how stupid, yet how faithful. How courageous! Our deaths are so beautiful, and yet somehow we are immortal, as we hear in the opening song: Poland has not yet perished / So long as we still live… A nation without a brain, without politicians, mindlessly walking towards their undoing, towards their death – a nation of only hearts and heavy hands, ready to fight’ – wrote critic Andrzej Jarecki in Sztandar Młodych daily after the premiere of The Ashes – a film Zygmunt Kałużyński called the last work of the so-called Polish Film School and its recapitulation, which gave it ‘a monumental truth and historical perspective it lacked before.’

Adapting Żeromski’s epic, Andrzej Wajda underlined that the most important scenes are ‘absurd and heroic at the same time, as many moments in our history.’ He has shown this paradoxical, contrapuntal approach to national ‘sanctities’ many times, in films such as Ashes and Diamonds, Lotna, and Kanał – all of which featured protagonists who paid the highest price for fighting for a just, yet lost cause. ‘I don’t pick Sienkiewicz to adapt, but Żeromski, because I am not interested in the literature of national agreement, a literature seeking to reconcile everyone with everyone,’ said the director about his choice. The film, which stirred up a hornet’s nest and challenged the essence of patriotism, was debated long after its premiere by historians, critics, and journalists. ‘Sienkiewicz’s healthy patriotism was then recognized as the model. Explaining that the criticized scenes, situations, and dialogues were not taken from Sienkiewicz, but from Żeromski, was futile. Nobody wanted to check this. Moczar and his people wanted to divide our society as quickly as possible, or at worst – to divide its elite into revisionists and true patriots. That’s how I became a revisionist, and that wasn’t helpful when trying to make more movies,’ Wajda recalled many years later.

The Ashes was the director’s ninth feature film, and at the time of its premiere, it was one of the most expensive movies in the history of Polish cinema, alongside Pharaoh and The Saragossa Manuscript.

The film was problematic from the start. Noble Poland, with all its attributes and iconography, ceased to exist after the 1944 land reform and the destruction of tens of thousands of manors. The first task before shooting was research and the reconstruction of everything, from historical costumes to hunting dogs, from weapons to locations. Private collectors helped the director, as well as horsemen who brought their horses from all over Poland and – lacking professional ones – served as stuntmen in the battle scenes, treating their charge as honorary service. For example, before shooting the scene of the Battle of Samosierra, a lot of controversy surrounded the scene in which a live horse was thrown from a cliff to film its brutal death.

Years after the premiere of the film – which entered the canon despite all the critiques – Wajda spoke about his mistakes during the shoot and what he would change. While Daniel Olbrychski’s role turned out to be a bull’s-eye and launched the young actor’s career, the director regretted listening to emotional fans and advisers who urged him to cast Bogusław Kierc in the role of Krzysztof Cedro instead of Zbigniew Cybulski. ‘Zbyszek would have been a wonderful Cedro, yet I chased young actors, hoping for a successful film,’ he recalled. He also concluded that making the film in black and white had been a mistake. ‘We feared color at the time; we were anxious that the costumes, the grass, the sky, and the architecture would not form one cohesive picture, that we would be able to artistically control it. Yet now I believe struggling with color film might have been a spur for our imagination. It was in fashion at the time to make widescreen films with anamorphic lenses. This format was never natural; it fought with the editing process because instead of making many takes, we shot the whole scenes in one long take, which made it impossible to accelerate the film’s rhythm…’

Despite these opinions, The Ashes is perceived as a courageous and outstanding film, polemical with the official, ‘polite’ versions of Polish history. Tadeusz Miczka wrote: ‘The quarrel over the appropriation of The Ashes lasted for three years. During this debate, which was the most turbulent discussion about any Polish film since after the war, emotions ranged from hysterical requests from appalled viewers and critics to burn Wajda at the stake, to thanks given to the director by the film’s enthusiasts, for creating a genuine version of the nation’s birth. For some, the film was the greatest historical and artistic lie in history, while for most, it was a great, sincere interpretation of past events.’

‘It was me who came to Jerzy Andrzejewski with the idea for a movie about the Children’s Crusade as the topic for our next film. As usual, he was enthusiastic,’ said Andrzej Wajda about the beginnings of Gates to Paradise. Indeed, it was the director who introduced Andrzejewski to the subject that had fascinated him for years: the medieval Children’s Crusades (German and French), based on the idea that only pure, innocent children could free the Holy Land from the Muslims. The fate of the crusaders was tragic: before reaching their destination, the children died from exhaustion and illness or were captured and violated.

The initial foundation of Andrzejewski’s script involved setting the film in early medieval Silesia. ‘This poetic, dramatic story with characters on the edge of the abyss, thrown there by magnified, wild passion, is very close to my heart and is a natural consequence of my interests,’ the director explained. ‘I am also attracted by the visual side. A never-ending procession of children through vast woods and fields, few props, and modest costumes make this film very different from a serial production of historical images, bringing it closer to modern problems of contemporary cinema. This story, which seems so distant, as if it was taken from old chronicles or even fairy tales, is a beautiful subject and, for that reason, I think worthy of being made into a film.’

Wajda said that Gates to Paradise gave him so much hope that it could have been the film he dreamt of the most. Yet, he couldn’t realize the idea he had prepared for so long. The commission that evaluated the script of Gates to Paradise in 1963 did not approve the application to send the project to production, justifying the decision with the fact that the subject was too distant from current affairs (a topic which was part of the program of Kamera Film Studio, the producer applying for the evaluation), and that it was impossible to translate the script into cinematic language (many retrospections and internal monologues could potentially limit the audience to intellectuals). The text was also accused of pessimism and, indirectly, of the presence of controversial homosexual motivations. The commission deemed the project equally great and risky, while Minister Zaorski, who chaired the meeting, deemed it impossible to reach a conclusion. Thus, making the film in Poland was put on hold, but Wajda was far from giving up.

His determination led to a British-Yugoslavian co-production, but he was not satisfied with the result.

‘The rejection of this project by the Polish cinema caused the delicate, poetic matter of Gates to Paradise to become an object of the brutal reality of an international co-production,’ he recalled. ‘Dialogues were translated into English, and I would never learn whether they transmitted anything but their pure content. Young actors were called, among whom only Mathieu Carrière had Schlöndorff’s beautiful film Young Torless behind him. The two male leads were played by actors I had known from Polański’s films, who wanted to help me in this difficult situation. In the end, Yugoslavia became the location. Rocky mountains dominated the whole film, giving the impression that the crusade, which marched for weeks, just stays in one place. (…) Now, when I look at the photographs of the boys’ faces, so beautiful and pure, when I go through ideas I sketched on pieces of paper, like Blanka’s hair which devours Aleksy’s head or two boys dressed as angels who carry a third one whose wings are broken; finally, when I go back in time to awe-inspiring Yugoslavian landscapes that are now ruined, it’s so hard to understand why I wasn’t able to show all of it on screen. I just have one answer. I trusted a group of random people – producers, actors, technicians – with my intimate dreams, and they reduced it to a minimum, to their own tastes and their own level, and I was completely helpless.’

His words are confirmed by the reviews, especially this excerpt by Claude Michel Cluny:

‘Andrzejewski’s novel has been noticed for two reasons. One: it consists of two sentences, one of which is a hundred-plus pages long, and the second – a few words long. Two: the book is marvelous. The filmmaker’s experiment is the answer to the writer’s experiment. Yet unfortunately, the book’s power and its tough greatness have not been equaled by the cinematic translation of its carefully chosen words, which expressed powerful passions, mixing exaltation with disappointment and fiery love which grew with every step towards the East with death. Each mind’s vision is turned into its visual equivalent. Illustration and interpretation narrow the imagination, imposing just one point of view. The creative element is reduced. Wajda betrays the original by remaining faithful – that’s the eternal reason for failure in the process of translating one art into another.’

For many, Everything for Sale remains Andrzej Wajda’s most personal film and one of the greatest works of autobiographical fiction in the history of Polish cinema. It is a film-essay attempting to capture ‘death in progress’ and understand the phenomenon of a man by confronting his sudden absence. The spark for the film was Zbigniew Cybulski’s tragic death; in the film, which premiered two years after his passing, shock dominates, along with a surreal feeling caused by the ontological absurdity of death – intensified by the presence of someone who suddenly becomes forever absent.

‘I always wanted to work with Cybulski; he only played in four of my films, yet I was also lucky enough to work with him in the theatre. Zbyszek was not just an actor, but also a personality worth showing on screen. One evening, on January 9th, 1967, in London, I spoke about such a film with David Mercier. He knew Zbyszek well, so we had a lot of fun, remembering anecdotes around which we could build the script. Late at night, when I went back to my hotel, Roman Polański called and told me Zbyszek was dead. That night, his death seemed unreal to me; I needed time to understand it wouldn’t change, that he would never play in any of my films again,’ Wajda recalled.

He began shooting with the conviction that he was making a film about Cybulski – attempting to capture the essence, the traces, the remains of a man who was no longer here. He knew that it wouldn’t make sense to talk about Cybulski using archival materials and photos of him. The film he decided to make turned out to be a story about Wajda himself and others who were suddenly orphaned and unable to comprehend the absence – the irreversible disappearance of someone so important to them. They try to express their pain and feelings, disclosing their emotions in the process. The boundary between privacy, truth, and artistic fiction becomes fluid and blurred.

‘It’s intentional that they appear under their own names,’ said Wajda about the actors in Everything for Sale. ‘Why would I give them different names if I make them say their own words? They say what they want to say. From the very beginning, I knew exactly who should star in this ‘sale’. The only problem was the part of the director. To be honest, there was a time when I thought I should play him, but I decided against it. I am not an actor, and I would never do it as well as Andrzej Łapicki (…)’

The film not only unveils the emotions of the people who, by playing themselves, lived their own private mourning, but also Wajda’s own indecision about the role art should play when confronted with reality and the limits of performance. This can be seen in the (auto)ironic portrayal of the film community. Wajda scrutinizes the parties, snobbish trends, and the general mendacity of his contemporaries. The protagonists of Everything for Sale are mannered and false; they’ve lost everything that was truthful about them.

What’s symptomatic is that the director, Andrzej, finds shelter from an overwhelming void in an art gallery. It’s telling that the works exhibited there are paintings by Wajda’s prematurely deceased friend Andrzej Wróblewski, who created a shocking series on the nightmare of war. ‘Remembering the past, a sense of mission, and a need to find the truth are all features of an old model of art that was never forgotten by the director of Everything for Sale,’ wrote Robert Birkholc on Culture.pl.

Confronted with loss, trying to redefine the sense and limits of creation for himself, Wajda made a deep, multilayered, and surprisingly accurate film about the relationship between art and reality. ‘In Everything for Sale, action is often paused,’ wrote British critic Philip Strick. ‘The grinding sound of train wheels in the first scene echoes throughout the whole film, as cars, parties, projects, and human interactions are stopped. Two contrasting images return as a chorus: a merry-go-round where Ela sits among a crowd of sophisticated film people she hates, and the pulsating gallop of horses (running in a circle) that measures the rhythm of the film, and finally ends it. Wajda’s commentary is a paradox: although everything stops when a person dies, life goes on, whether we like it or not. And so, the second layer of Everything for Sale is a synthesis of a director in general, and Wajda in particular. Everything the protagonists possessed (or imagined possessing) was for sale and was sold; now Wajda even sells Cybulski’s death and his own resignation from finishing the film for cinema’s greater glory.’

Przekładaniec (Roly Poly) is an unusual film in Andrzej Wajda’s filmography. However, when viewed in the context of its time, its genesis becomes more understandable. By the time Wajda began making the film, he was already an established director both in Poland and in Europe. He was looking for new experiences in genres, means of expression, and subjects that went beyond the interests of the Polish Film School, particularly the experiences of war. In the 1960s, Wajda was constantly on set – making films like Samson and The Ashes, which were deeply connected to Polish national identity, but also more contemporary films, such as Innocent Sorcerers and Love at Twenty. He also engaged in international co-productions based on literature (Siberian Lady Macbeth, Gates to Paradise). Right before Przekładaniec, Wajda made one of his most intimate and painful films, inspired by a personal loss – Everything for Sale – and followed it by adapting Lem’s work, Hunting Flies. Many critics have described the 1960s as the time when Wajda was searching for a new cinematic language to address a changing world – one that was shaking off the trauma of war and focusing more on human relationships, a growing consumerism (both at the societal and interpersonal levels), and a crisis of values.

The 36-minute film, based on a script by Stanisław Lem entitled Do You Exist, Mr. Johns?, is Wajda’s first comedy, his first television film, and his one and only sci-fi film. It is surprisingly ironic and brilliantly executed. When Wajda asked Lem for permission to adapt his text, Lem prepared the script on his own. It was published as Przekładaniec in the Ekran monthly in 1968. The texts are only slightly different, mainly because the original story focuses on cybernetics, while the film script shifts focus to transplantology, a new science at the time that was both controversial and fascinating.

Stanisław Lem, who was openly critical of adaptations of his work (Kurt Maetzig’s The Silent Star, Edward Żebrowski’s Hospital of the Transfiguration, Marek Piestrak’s Inquest of Pilot Pirx, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris), not only accepted Wajda’s version but even praised it: ‘Wajda’s film with Kobiela in the leading role is probably the only adaptation of my prose that fully satisfies me. The first source of this satisfaction comes from the film’s internal construction. Wajda admitted that he tried to rebuild my script by rearranging the blocks, but it turned out to be impossible; it was satisfying for me as a constructor.’

Not long after the premiere, Lem wrote to Wajda: ‘Your work, the actors, as well as the set design, all seemed very good to me. I particularly liked the lawyer; the surgeon seemed very nice, and not to mention Kobiela. (…) The future, which is close yet undefined, was created very ingeniously, especially given how modest the means you used.’

Despite being just a low-budget TV film, Przekładaniec received many awards, including recognition from the typically insular sci-fi world. It also showcased Wajda’s versatility, creativity, and instincts. He was able to craft a true visionary cinematic gem with the help of his crew. The film’s futuristic style was inspired by comic books and pop art – the drawings and fonts were created by lettering and magazine designers Elżbieta and Bogdan Żochowscy. Andrzej Markowski, who had worked on over thirty movie soundtracks, was responsible for the sound design, which featured many effects and jazz motifs. Wajda had already collaborated with him on A Generation. The costumes were designed by Barbara Hoff, who was famous for designing popular clothes for Domy Handlowe Centrum department stores.

Bogumił Kobiela, playing the role of rally driver Richard Fox (who has accidents in every race and forces doctors to transplant more and more organs from deceased donors, raising questions about his identity), delivers a true tour-de-force performance. Legal and ethical dilemmas are explored through Fox’s lawyer, played by Ryszard Filipski. Wajda was so impressed with Kobiela’s performance that he stated the film could easily be adapted into a full-length feature. Tragically, the role in Przekładaniec turned out to be one of Kobiela’s last triumphs, as he died in a car crash less than a year later – an ironic postscript to the film.

Film critic Małgorzata Bugaj summed up the project in her 2018 text Wajda autoironicznie: Lem i Przekładaniec (Wajda and Self-Irony: Lem and Roly Poly): ‘Considering the experiments of the 1960s, we can speculate that the gradual loss of ‘self’ of the main protagonist is a reflection of a certain deadlock in Wajda’s artistic and personal life. This deadlock added layers to his identity, which was established earlier. The cover granted by the genre and a sense of humor allowed for a self-ironic distance and a summary of achievements at a moment of crisis, which preceded the opening of a new chapter in the director’s career.’

Hunting Flies is considered an oddity in Andrzej Wajda’s body of work and is his only true comedy, even though comedic elements appear in Roly Poly, as well as in Pan Tadeusz and The Revenge. The story told by Wajda is an adaptation of a short story and the first script by writer and playwright Janusz Głowacki, who reverses the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea. In this version, it’s the young woman who shapes the older man to meet her requirements, expectations, and fulfill her dreams.

Wajda connected the genesis of Hunting Flies to his own personal, sentimental struggles. He explained: ‘Without thinking much (…) embittered by my temporary failures, I decided to tackle the subject of women trying to shape our male lives. As is typical in such hopeless situations, the beginning was promising. First of all, Małgorzata Braunek turned out to be a great choice. Her wide grin and eyes enlarged by unnaturally large glasses seemed to leap off the screen and perfectly illustrated the cruel fly drawn by the screenwriter. If I were to further explore the psyche of my man-eater, I could have achieved a lot. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a male partner. Initially, I thought of Kobiela, even inviting him for a test. But my temporary disdain for women clouded my judgment, and I convinced myself that only a complete nobody could be controlled by a woman the way Janusz Głowacki presented it in his script. I decided Kobiela was too interesting for that, too expressive. In retrospect, I’m certain that only his humor would have saved the film from me and my self-righteousness. I lacked distance and had to pay for it…’

Wajda took to heart the criticism of the film, with many accusing him of not finding his place in the genre of satire. The film was called ‘quite pale’ by some. After the premiere, critic Jerzy Płażewski wrote: ‘A funny satire doesn’t require one-sided scrutinizing of its protagonists, nor treating them like idiots (…) Wajda looked for satire in the wrong place. He searched for it in caricature and simplification, which didn’t make the film funnier, but instead limited the extent of issues it could address in Hunting Flies.’

The director later admitted that casting Zygmunt Malanowicz, who had no prior acting experience, as Włodek – mostly due to his looks – transformed the film. What was originally meant to expose the cruel and manipulative nature of women turned into an exploration of the crisis of masculinity. The Warsaw bohéme, which Włodek aspires to join under the influence of his young lover, also saw itself reflected in the film, like a mirror revealing its own smallness, deficits, and pretentiousness. The portraits, observations, and tidbits from the life of Warsaw’s ‘glitterati’ are especially interesting to modern viewers, who can now see them as a testament to the social condition of the time.

What did impress audiences, in contrast to the passive, unhappy male protagonist, was the character of Irena – the nightmare of every man: an independent, cynical man-eater. She is possessive, vain, exalted, and manipulative – both fascinating and repulsive. As a result, Małgorzata Braunek undoubtedly took advantage of the opportunity presented by this ‘failed’ film and created one of her most significant roles, demonstrating her full potential.

When watched with the benefit of time, Hunting Flies paradoxically does fulfill Wajda’s initial intention: men and women live in illusions about themselves. They see projections of the partners they wish to have, not the people they truly are.

‘Among many Polish literary masterpieces about the war, Zofia Nałkowska’s Medallions and Tadeusz Borowski’s This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen hold a special place. When I read them, even today, I am overtaken by fear. A man knows so little about himself until he finds himself in such situations. None of these stories were adapted to the screen – perhaps because their depiction of war left no illusions about human nature. The Battle of Grunwald is penetrated by this bitterness – although it is set in post-war Germany, in a camp for the so-called DPs. Pre-war Poland fell apart in 1939 in front of our very eyes. The disillusionment with old Poland that we experienced at the time shaped the mood of the post-war intelligentsia, leading to its initial affinity for the new authorities. I think that is why Borowski’s bitter irony was so close to me. I could have easily imagined his short story as part of my own life. That’s why, as soon as I could, I did everything in my power to bring The Battle of Grunwald to the screen’ – Andrzej Wajda recalled the inspirations that led to making Landscape After the Battle.

The script was based on Tadeusz Borowski’s short story Battle of Grunwald, but the co-writer, documentary filmmaker Andrzej Brzozowski, and Wajda decided to incorporate motifs from several other stories by this author. The subject, based on drastic wartime prose, did not attempt to express the inexpressible – the Holocaust itself – but rather focused on life after the Holocaust and the process of reconstructing one’s identity, fighting trauma, and the possibility of adapting to an ‘afterlife’, when confronted with total disillusionment with human nature. Wajda’s film is filled with a sense of emptiness, bitterness, resignation, and the loss of humanity. Even though the protagonists were freed from the German camp, they are still kept there – as in a transit camp – waiting for the difficult, yet desired moment of confronting freedom.

The director noted that this moment immediately after the war was depicted not only by him and Borowski but also by painter Andrzej Wróblewski, whose work is quoted in the frames of Landscape After the Battle. Wajda, who always considered it his duty to speak in the name of the dead who could no longer raise their voices, decided this time to focus on the state of mind of those who survived but whose psyche had been broken by the war – a war that put an end to everything they believed in – and who were now confronted with the need to learn how to feel again. Both Wajda and Borowski seem to suggest that love could be an antidote to trauma and hopelessness, yet paradoxically, this love will once again be accompanied by death.

The leading roles in Landscape After the Battle were played by Daniel Olbrychski, who was a close collaborator of Wajda after The Ashes, Everything for Sale, and Hunting Flies, as well as debutante Stanisława Celińska. The film demanded great dedication from her, especially with regard to demanding sex scenes, which she prepared for by coming on set with a sex manual, shocking the nervous Olbrychski and Wajda. After the premiere, in addition to an award at the Łagów Film Festival, the young actress received letters from men interested in an intimate relationship. At the same time, she raised the bar very high for herself – at the Cannes festival, she was compared to Monica Vitti.

Melchior Wańkowicz wrote in a review for Kultura: ‘There is passion in the film, which at first glance seems distant from social issues. It’s a loving embrace between a boy and a girl, who are freeing themselves but are not yet free. (…) I read it as a symbol. I read it as Mickiewicz’s lava, which sticks to the bitter girl, to the sceptic boy. A surreal image of two bare bodies transforming in a multiplied twist on the ground, lined with (under some dried leaves) sharp twigs and pebbles that scratch, cause pain – a pain that accompanies liberation. Maybe that’s a symbol Wajda didn’t even intend to put there? (…) This beautiful image of love can symbolize human mulch from the barracks. The shell of humiliation will fall, but will creative fire burn? (…) I think Wajda caresses. He is not alone. He is standing on the shoulders of our greats. Żeromski scratching wounds, Matejko criticized for the bitter message of Rejtan, Chopin with his sadness. The revisionism of the Kraków history school. That’s a powerful background.’

Landscape After the Battle won, among other accolades, the Złota Kaczka prize from the readers of Film weekly for Best Film of 1970 and the Syrenka Warszawka prize from critics. Andrzej Wajda also received top prizes at film festivals in Milan and Colombo, as well as at the summer film festival in Łagów.

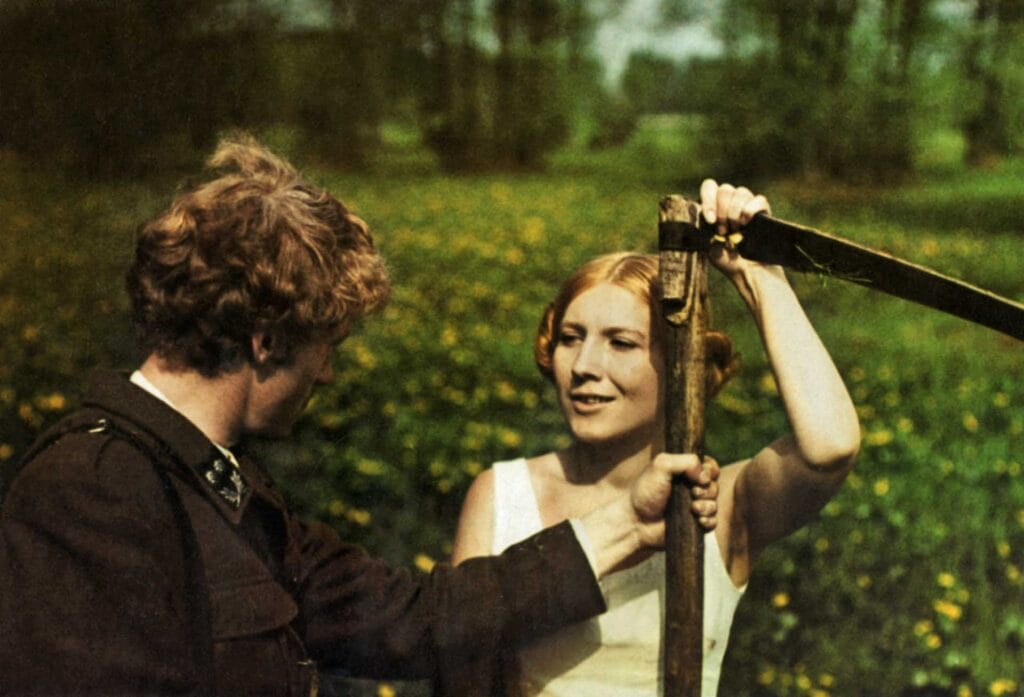

‘I am not a stranger to emotions awakened by the beauty of nature. In particular, I remember the first feelings from my childhood. But then, busy with making films and sitting in dark theatre rooms during rehearsals, I had no possibility to notice the changes in nature’s repetitive cycle. Either I ripped the leaves off the trees – as in Ashes and Diamonds – because it was already summer, and I needed an early spring, or I glued them on, because I didn’t make it in time for summer, and autumn had begun – as was the case with Landscape After the Battle. To be fair, I could only closely observe something through the lens of a camera, and that’s why I only saw real spring once in my life. I had known Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz’s short story for a long time, yet I needed to grow up to the selflessness of its subject. Polish Television helped me by ordering The Birch Wood’ – wrote Andrzej Wajda about the beginnings of adapting Iwaszkiewicz’s story.

‘After the first few days, the crew, used to the stuffiness of film studios, could barely stand the crystal-clear morning air – it was a shock for many of us. It wasn’t a surprise that one day the key grip asked me for a cigarette, saying: ‘This fresh air is killing me…’. We joked that it was oxygen poisoning. Under the influence of this incredible drug, we made a film that felt different: fresh and surprising, even to me. The air entered my lungs, I felt lighter, and I looked at the screen in awe, as if it wasn’t mine. Some of its freshness remained, both in the actors’ and cinematographer’s work’.

Andrzej Wajda employed Zygmunt Samosiuk to shoot the film, having noticed his talent while watching film chronicles and a reportage where the cinematographer filled each frame with falling snow. To Wajda, this meant he was a master in cinematography and worked quickly. Edward Kłosiński, Samosiuk’s younger colleague and assistant, also worked on the film, later becoming Wajda’s collaborator and friend for many years. Partly due to Samosiuk’s work, The Birch Wood is considered one of the most artistic and visually stunning films by the director. Wajda, who studied to be a painter, filled The Birch Wood with a network of associations and references to paintings – in this case, mostly by Jacek Malczewski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and Aleksander Gierymski. Many frames are direct transpositions of paintings such as Self Portrait with Thanatos, Death, The Poisoned Well, and Narcissus.

Despite some slight changes to the literary original, Wajda succeeded in preserving the soul and depth of the story. The actors also contributed: Daniel Olbrychski and Olgierd Łukaszewicz, who created a moving portrait of a man saying goodbye to life in his prime. ‘It’s sad to die on a bright day in the spring,’ wrote Wajda. ‘To pass, when so many incredible things are happening in the natural world. To me, Jacek Malczewski was the one to show this phenomenon with his paintings of death waiting behind the window in the garden. I am always moved when I think about this film – maybe because I made it for pleasure, not thinking about its potential success. I knew there were a few things I should do in my life and making a film in a birch wood is one of them.’

The consensus among Polish and international critics was favorable toward The Birch Wood. They wrote that it was a film ‘woven with both violence and fragility, force and passion, with acceptance of fate and tears, a passion for life even in a world that’s so poorly organized, against the certainty of death’. It was called ‘a film pulsating with agony, the last gesture of life, life itself’, and praised as ‘Wajda’s look at the essence of human fate’. Iwaszkiewicz himself wrote to Wajda about the Paris premiere: ‘It was a great joy for me, because I really like this short story, written 45 years ago, and I believe that you did it magnificently. As they wrote in the New York Herald, ‘you were faithful to Iwaszkiewicz’s spirit.’ And all that’s yours (Malczewski, the whole of Easter) is so beautifully combined with what’s mine. I am very grateful for all of that and remain an admirer of your intuition, your work, and everything that made my story into your movie.’

When Andrzej Wajda began thinking of a story about Pilate, he tried to interest poet Zbigniew Herbert, who was living in Berlin at the time, in a collaboration. This creative team might have come together had it not been for Herbert’s commitments in the United States. ‘I wasn’t satisfied with the first two versions of the script I ordered in Warsaw. Fortunately, at that time, Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita was published in Polish for the first time. I read it in awe. It became obvious that I wouldn’t find a better text for my movie than a novel about Pilate. I had everything: Jesus, Pilate’s dark intrigue, Judas’s treason, and the overwhelming loneliness of the only student and Evangelist,’ wrote Andrzej Wajda about the preparations for Pilatus und Andere, a film for the German ZDF television channel, which granted him complete artistic control over the project.

Four out of the thirty-two chapters of The Master and Margarita, based on the Gospel of Matthew, were a precise, concise, and moving chronicle of the protagonists’ last hours, which Wajda wanted to explore. However, he decided to move the plot away from its original setting. While in Nuremberg, Wajda saw the ruins of a Third Reich congress hall, and his instincts told him that this contemporary setting would serve as the perfect commentary on the story of a murderous empire, like ancient Rome two thousand years before. ‘Shooting on the tribune where Hitler spoke during the NSDAP party conventions was particularly moving. We were part of the Slavic nations that were supposed to be destroyed to make Drang nach Osten possible. Yet here we were, healthy and alive, in the ruins of the Third Reich – and we were making a movie! When we were working on Pilate, I felt so free. I have never forgotten that personal and artistic freedom,’ the director wrote in his diary after the shoot.

The Way of the Cross was filmed on the streets of Frankfurt am Main, and a garbage dump near Wiesbaden served as Golgotha. The camera didn’t shy away from filming the observers who gathered to watch the movie set. Wajda designed the costumes himself. They were an eclectic mix of styles and historical elements with modern clothes and everyday objects. For the soundtrack, in addition to natural sounds from contemporary locations, The Gospel of Matthew by J.S. Bach played. ‘I show tourists who jump to a bus’s windows to catch a glimpse of the execution,’ recalled Wajda. ‘Yet a modern highway has its own rules, the signs which forbid cars from stopping, solving a moral issue. If we crucified a man to the cross with real nails, their reaction would be the same. What can you do for a suffering man, how can you help him, if the car cannot stop anyway? I think the film was successful in showing this sadness of indifference and the loneliness of death.’

Wojciech Pszoniak as Yeshua Ha-Nozri and Jan Kreczmar in his final role as Pontius Pilate gave memorable performances. Daniel Olbrychski, Marek Perepeczko, Andrzej Łapicki, and Wajda himself – as a reporter – also appeared in the film.

The film was first screened on Good Friday, March 29th, 1972, on the second channel of German television. Wajda, who received the prestigious Western-German Bambi award for the production, considered this the end of its road. However, the director was determined to screen the film in Poland, especially given how popular Bulgakov was. He succeeded in his plan three years later. The film was shown only in arthouse cinemas, on just two copies, but the interest was immense. Yet, recommendations were soon issued by the Main Office for the Control of the Press, Publications, and Performances, forbidding the dissemination of information about the film, including reviews, articles, and overviews; only information about screening times was allowed.

In Germany, the film received mixed reviews. Some critics found it too eclectic and extravagant, while others believed it was filled with suggestive symbols of modernity that helped a 20th-century audience understand the tragedy of Good Friday, which is the foundation of European civilization.

‘Many years after the premiere, in Paris, I met Elia Kazan, a master of American cinema. When I told him my name, he asked, ‘Are you the director who made the movie that takes place in one night?’ I instantly thought he meant Ashes and Diamonds. But he was referring to The Wedding. He asked me who wrote such a wonderful script for me. I was happy and proud that I could give cinematic shape to a theatre play and that Elia Kazan looked beyond the brilliance of Stanisław Wyspiański’s play,’ recalled Andrzej Wajda.

The Wedding is considered one of the most original plays ever written in Polish, and it would be hard to find an important artist who hasn’t drawn inspiration from Wyspiański, borrowed motives, or directly referenced his play in their own work. It is also one of the most analyzed Polish literary texts, often studied in the context of its adaptations. Universally regarded as essential to Polish culture, it addresses issues of national identity, freedom, and historiosophy. At the same time, it delves into the nation’s complexes, weaknesses, and character traits, which have led to its ruin time and time again.

Adapting it to film seemed almost impossible. However, Wajda had mentioned the idea of a film version to Stanisław Janicki as early as the 1960s. He even adapted the play for the stage at Teatr Stary in Kraków in 1963. The first attempt to film The Wedding, based on Andrzej Kijowski’s script, which moved the action out of the house in Bronowice and placed it around Kraków, was abandoned after four weeks of shooting. Wajda realized that only the unity of action, time, and place could ensure the proper dramaturgy and condensation of the plot. From those early days, only the introductory sequence, the procession scene from the church in Bronowice, and the scene of the failed insurrection remained in the final cut.

The finished film was shot entirely inside a hut with movable walls, constructed in a studio. Set designer Tadeusz Wybult was asked by Wajda to further move the walls so that the rooms seemed even smaller. This, combined with Witold Sobociński’s dynamic cinematography and the colors he envisioned, created an effect of constant movement, like a dream-like, vertigo-inducing trance. The camera flowed to the rhythm of folk music, as well as a score composed by Stanisław Radwan. Additionally, the hypnotic, sharp voice of Czesław Niemen, whom Wajda cast in the role of Chochoł, added to the film’s atmosphere.

Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz wrote about the film in Miesięcznik Literacki: ‘As every director adapting a play to the screen, Wajda needed to ask himself one question: not wanting to destroy The Wedding, how could he break through its staginess, its theatrical unities, its divisions into scenes and acts, and the conventionality that cinema hates? The task is even more difficult in The Wedding, since the protagonists speak in verse. If they didn’t, it would be an offence to everything the modern audience remembers. Wajda’s response to staginess is reality. The film doesn’t try to make the play more colorful or dream-like, but instead makes the reality of the drama more concrete, material, and touchable. The reception room is small, stuffy, crowded; the hall is narrow; the courtyard is muddy and ugly; and the Host’s canvases are lying around in a shed next to barn equipment. Theatre doesn’t happen in such an environment; life does, and that’s what the film does. […] That’s what The Wedding is: some peasants, some writers, a councilwoman – and suddenly, one of the most important things ever written in Polish appears.’

While the film received mixed reviews, it was clear from the start that it was an unprecedented achievement in Polish cinema – revolutionary in its form and in how it adapted a theatrical play. Its most important feature, however, was its condensation of symbols, myths, and historical figures into a chaotic dance that tells the tragic story of Polish national identity and collective ignorance in just over a hundred minutes.

Raymond Lefévre, reviewing the film for the French press, summarized his impressions: ‘This masterpiece by Wajda takes us right to the heart of Polish reality. At first glance, it brings us a joyful atmosphere that the camera joins without restraint. As if it were an invited guest, it clings to pirouettes, gets drunk on folk music, joins conversations, underlines responses, analyses faces, and then joins the dance again. Tireless, interested, mad, but hopelessly sharp. That is Poland caught in its contrasts. […] Poland, drunk on alcohol and words, made ill by its master’s cravings and ridiculed heroism, stuck in resignation and Catholicism, as the messenger gallops through a country that does not exist. This wonderful allegory somehow reconciles baroque and acuteness. It is far more convincing than any consciously didactic discourse.’

Today, The Wedding is considered one of the masterpieces of Polish cinema, both in Poland and internationally.

There’s a funny anecdote connected to the beginnings of The Promised Land that Andrzej Wajda recalls: “Tired and dissatisfied, in the spring of 1973, I turned to housework. Krystyna (Zachwatowicz – Wajda’s wife) had just sown the lawn and, as the experts advised, I started cutting it with scissors. On my knees, I had worked through a patch barely larger than a table when I decided: I prefer making movies. Suddenly, I felt lighter and brighter. I submitted the script of The Promised Land. It was well received, and in the summer, we started shooting. A great adventure began with a city that uncovered new fragments of its incredible past every day.”

It was Andrzej Żuławski who gave Reymont’s novel to Wajda and also showed him a documentary by Leszek Skrzydło about the palaces of factory owners in Łódź. These buildings, untouched by the war, were still incredibly impressive and became natural sets for the film. Wajda was so enthralled by the possibilities Łódź offered that he quickly began preparing for the shoot—especially since he already had a script. He had written the first draft in 1968, but it wasn’t until 1971, when the X Film Studio opened and he became its chair, that he received official permission to start production on The Promised Land.